The Major Importance Of Being Someone Like Earnest

I knew that Oscar Wilde wrote a four-act version of The Importance Of Being Earnest, but I'd never known why he changed it to three. Now that I've read the definitive four act edition, edited and introduced by Ruth Berggren, the whole thing is clear.

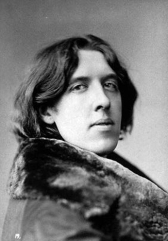

It's 1894 and Oscar Wilde needs money. Sure, he's had recent hits on the West End, but he lives extravagantly (egged on by lover Lord Alfred Douglas). His previous hits have

been melodramas leavened by his wit, but his latest is a farce, and he thinks his best work yet.

been melodramas leavened by his wit, but his latest is a farce, and he thinks his best work yet.He writes to actor-manager George Alexander, who starred in Wilde's first big hit, Lady Windermere's Fan, and asks for some front money. Alexander seems willing but they run into a snag. Wilde--who, by the way, employs a newfangled typewriting service for clean versions of his work--has written a four-act play. Alexander needs something with three acts. (He also wants one he can play in London then tour in America, though Wilde would rather sell the American rights separately.) Alexander, running a top-notch commercial theatre, plans to have a one-act curtain raiser to allow fashionable latecomers to settle in.

So Wilde sells the rights elsewhere while Alexander puts on a piece by Henry James. Which flops. Alexander needs something new quick, so he buys the rights to Earnest, but insists on changes.

The changes aren't just to shorten the play, however. In the original version, the two male leads, Jack and Algy, are equal roles. Much of acts two and three (which in the three-act version are squished into one act) are Algy's romance with Cecily. Plenty of the trimming is done to make the play more effective, but a lot of it helps make Jack the unquestioned lead. Alexander was a star and would insist. About half of Algy and Cecily goes, not to mention a fair amount of the secondary characters Prism and Chasuble.

There's also a lengthy scene where a new character, Gribsby, comes to Jack's country home to collect a debt Jack piled up in London, and that he believes, due to farcical complications, Algy must pay. There's some nice material that must have hurt Wilde to cut.

[After Jack discusses the idea that incarceration might be good for Algy]

Gribsby: I am sorry to be forced to break in on this interesting family discussion, but time presses. We have to be at Holloway not later than four o'clock, otherwise it is difficult to obtain admission. The rules are very strict.

Algy: Holloway?

Gribsby: It is at Holloway, sir, that detention of this character takes place always!

Algy: Well, I really am not going to be imprisoned in the suburbs for having dined in the West End. It is perfectly ridiculous! What nonsensical laws there are in England!

Furthermore, Jack is made--somewhat--the more responsible and romantic of the two. While all the major roles are excellent,

any major production--John Gielgud's, for example--will have the top male play Jack.

any major production--John Gielgud's, for example--will have the top male play Jack.Reading the four-act version is to glimpse an alternate universe. (Not unlike reading certain folios of Shakespeare that don't comport with the standard versions.) I know the three-act version backwards and forwards, so reading the same plot but with characters who have slightly different names and say somewhat different things is freaky.

Comparing the two versions, there's no question the final version is superior. Wilde may have been rewriting to Alexander's demands, but more important, he was polishing.

Along the way, the characters became more inhuman. This would normally be a bad thing, but Wilde tossing out all the small explanations and emotions found in longer lines makes the final version shine. Less explanatory, more epigrammatic. Less natural, more witty. Wilde's characters, so good with paradox, were never quite believable to begin with. Trying to humanize them will sink a production. Wilde moving the play away from nature (he'd been quarreling with nature for years in his philosophical writing) improves it immensely.

He also cuts to make the plot zoom. A lot of wasted motion is gone in the three-act version. For instance, in the final moments of the play, Jack quickly looks through the Army Lists to find his real name. In the earlier version, he hands books to every character and they all have their own lines about what they're reading before the name-confusion is resolved.

What sort of changes were made? You could write a book about it. But let's look at some examples.

In Act One we've got this line where Jack speculates about his love, Gwendolen, meeting his ward, Cecily:

Jack: ...Probably half an hour after they have met, they will be calling each other sister.

Algy: Women only do that when they have had a fearful quarrel and called each other a lot of other things first...

Which becomes:

Jack: ...after they have met, they will be calling each other sister.

Algy: Women only do that when they have called each other a lot of other things first.

Much better. Note Wilde doesn't feel the need to explain the line, make it more "natural"--he gives Algy the wit without the strain.

In the second act, we have this from Chasuble, the church rector, regarding Cecily's governess:

Chasuble: Were I fortunate enough to be Miss Prism's pupil, I would hang upon her lips. (Miss Prism glares) I spoke metaphorically--metaphorically! Ahem!

Not a bad line, but Wilde adds something:

Chasuble: Were I fortunate enough to be Miss Prism's pupil, I would hang upon her lips. (Miss Prism glares) I spoke metaphorically--My metaphor was drawn from the bees.

Wilde also follows up with similar metaphor-based lines, sharpening Chasuble's character as well as his dialogue.

Here's an interesting change from the final act:

Brancaster [Bracknell in the three-act version]: I dislike arguments of any kind. They are usually vulgar, and always violent.

Wilde knows this isn't quite right. By the time he's done, he's fixed it:

Bracknell: I dislike arguments of any kind. They are always vulgar, and often convincing.

Would Wilde have polished his play even if he didn't need to grind it down to three acts? Probably. We know he cut plenty of great lines even before he sent the four-act version to Alexander. But who knows how it would have turned out? We can be grateful that Alexander made demands that Wilde thought unreasonable at the time.

Algy: Women only do that when they have called each other a lot of other things first.

Much better. Note Wilde doesn't feel the need to explain the line, make it more "natural"--he gives Algy the wit without the strain.

In the second act, we have this from Chasuble, the church rector, regarding Cecily's governess:

Chasuble: Were I fortunate enough to be Miss Prism's pupil, I would hang upon her lips. (Miss Prism glares) I spoke metaphorically--metaphorically! Ahem!

Not a bad line, but Wilde adds something:

Chasuble: Were I fortunate enough to be Miss Prism's pupil, I would hang upon her lips. (Miss Prism glares) I spoke metaphorically--My metaphor was drawn from the bees.

Wilde also follows up with similar metaphor-based lines, sharpening Chasuble's character as well as his dialogue.

Here's an interesting change from the final act:

Brancaster [Bracknell in the three-act version]: I dislike arguments of any kind. They are usually vulgar, and always violent.

Wilde knows this isn't quite right. By the time he's done, he's fixed it:

Bracknell: I dislike arguments of any kind. They are always vulgar, and often convincing.

Would Wilde have polished his play even if he didn't need to grind it down to three acts? Probably. We know he cut plenty of great lines even before he sent the four-act version to Alexander. But who knows how it would have turned out? We can be grateful that Alexander made demands that Wilde thought unreasonable at the time.

4 Comments:

Actually, I was once in a performance of the 4-act version! What we did was compare it with the 3-act version, debate which version of each (similar) line we liked better, and then go with our favorite. Then we cut out some of the padding, and ended up with a modified 4-act version (performed in three acts.)

And I agree, the Gribsby parts can be very funny in performance (though some argue they make the play a bit more harsh and real, to its detriment.) But we definitely kept them, and loved them.

And though I wouldn't call Wilde's earlier successes melodramas -- they're very clearly comedies, albeit with touches of both sentiment and melodrama -- I do agree that Earnest feels like the purified Wilde. (But perhaps that's just how we see him! Certainly if one looks at all his works, Earnest is the exception rather than the rule...but one does feel that it's the pure him, with all that Victorian stuff burned away...)

Cara

His earlier hits are often called comedies, but the plots are pure Victorian melodrama.

I think Wilde knew how good Earnest was, but I believe he also resented people liking it to the exclusion of his other plays. Still, it's a rare, perfect work.

(Jack. You're quite perfect, Miss Fairfax.

Gwendolen. Oh! I hope I am not that. It would leave no room for

developments, and I intend to develop in many directions.)

Shaw, Wilde's only contemporary who could compare, wrote about 60 plays and none of them are perfect. Ironically, as a drama critic who'd greatly praised an Ideal Husband, he gave a rare thumbs down to Earnest. Some think it was jealousy, but I believe what he says--he found to play too frivolous. Shaw always had a didactic streak in him. Which is why it took him so long to get his plays onto the West End, and, perhaps, why he never wrote a perfect play.

I find it one of the most overrated plays in the language. If anyone but Wilde had written it it would have long since vanished, along with his appalling poetry. An Ideal Husband seems superior to me in every way.

The thing I most dislike about him are his aphorisms. They're all stupid and don't mean anything, and when I hear them quoted I want to scream.

The only thing worse than quoting Wilde's aphorisms, is not quoting Wilde's aphorisms.

Don't ask me why, but I was just looking over this old post and here's a new comment.

I agree with Matthew (who can certainly be a contrarian) on many things, but obviously not this.

I first read Earnest in high school. Like so many classics we were required to read, I feared it would be dry and filled with intricate language. Imagine my surprise when I found myself laughing.

The plot isn't bad, either. Better than the "well-made" earlier works.

But I do agree his poetry stinks.

Post a Comment

<< Home