It's Showtime!

Jerome Robbins left Broadway behind in 1964, during the age--that he helped start--of the director-choreographer. They didn't write the show, or star in it, but owned it nevertheless. And the man who became the top name in the field wasn't Gower Champion or Harold Prince (who didn't choreograph but sure knew how to stage) or even Michael Bennett. It was Bob Fosse, whose name became a style in itself. On top of that, he was the only one in this age who became a major Hollywood director. Most didn't, or couldn't, make the switch. (Robbins himself won an Oscar for co-directing West Side Story, but got fired from the film--his first--because he took too long to do the dances.)

And now Sam Wasson has a biography out befitting such an innovator, simply entitled Fosse. At 700+ pages, it has the room to go into detail for each major show and film the man worked on.

Fosse was born in Chicago June 23, 1927 (today's date, by no coincidence), and grew up, like so many, poor during the Depression. His dad was a show biz failure who put the bug into his son. Little Bobby took dancing lessons and was earning money at it by age nine. He became part of a team, the Riff Brothers, who performed their act during an age when Vaudeville was somewhere between dying and dead. Fosse, who'd go out on his own in his teen years, played up and down the Midwest in every cheap hall and theatre there was. He spent of lot of his time, in fact, playing in burlesque houses, being teased by the girls there.

This background played heavily in his later work, which was so often about the sleazy side of entertainment. (When you look at it, this is the theme of every film he made.) He developed a style in these years that played up his strengths and hid his weaknesses--the hunched shoulders, jerky movements, turned-in feet, cocked hat (to cover his thinning hair), not to mention the sly, sinuous, sensual movement that became a hallmark. His background also gave him a sense of inferiority--he didn't come from ballet, like Robbins. He came from the lowest rung of show biz, and always felt that he was a bit of an impostor--"fooled 'em again" he'd often say when a show was a hit.

He spent some time in the military, as a performer, and then in 1949 married girlfriend and dancing partner Mary Ann Niles. It was the beginning of a lifelong pattern--fall in love with a talented woman, be with her (sometimes marry her), cheat on her, and finally toss her aside for another. And Fosse had no trouble meeting women--he was cute, charming, talented, empathetic and, not so common among male dancers, decidedly heterosexual. He pretty much had his pick of the chorus.

He made his way to New York and was establishing himself as an entertainer when Hollywood took notice. MGM signed him to a contract in 1953. However, the big Hollywood musicals of the Freed Unit were on the wane and the studio didn't quite know what to do with him. They put him in a few films, and he's pretty good, but it's also clear he's not the next Gene Kelly or Fred Astaire. He's got moves, but not that star presence. He would later play lead in some stage shows, and consider doing more, but essentially from this point on he was a behind-the-scenes guy.

He got out of his contract and came back to New York. It was around this time that he left his first wife and took up with Joan McCracken, a top dancer who'd appeared in the original Oklahoma! She encouraged him, and pushed him, and soon he got a job choreographing a major Broadway musical, The Pajama Game. The show was special in that it had maybe the top four musical directors of all time working on it--Fosse, producer Harold Prince, director George Abbott and good old Jerome Robbins. Robbins was hired to spot neophyte Fosse--he was well-established and didn't want to just choreograph so Abbott agreed to name him co-director. Fosse, at this point, was good at small numbers--his "Steam Heat" is a classic--but he was still learning how to stage larger numbers, something Robbins was a master at.

During the 50s he'd go on to choreograph some other Broadway hits--Damn Yankees, Bells Are Ringing, New Girl In Town, Redhead--and win three Tonys. Most of these show featured Broadway sensation Gwen Verdon, who became his next wife. On that last show, he'd also become a director.

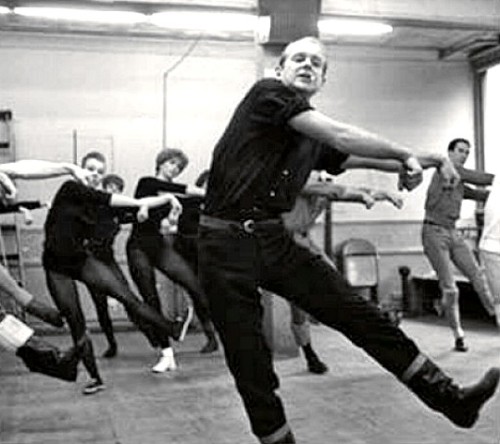

He worked his dancers intensely, searching for something that would play. He didn't just demand, for example, the arm be held correctly during a movement--he'd specify where the wrist, or a finger, should be. He was also known for his directions--he didn't want mechanical movement, he wanted each dancer to believe he or she were playing a specific character with specific motivations.

In 1960 he'd learn another important lesson when he was fired from The Conquering Hero (which would go on to flop) while out of town. (This was the show where bookwriter Larry Gelbart famously observed that the proper way to punish a Nazi was to bring him out of town on a musical). The show was based on Preston Sturges' wartime comedy Hail The Conquering Hero, and Fosse wanted to play up the political satire, making the show a bit harsher, not just another mindless Broadway musical comedy. His firing made him fight for more and more control, and also seek out darker and darker themes.

After taking over the choreography of How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying--a smash--and directing and choreographing Little Me, he was back on top. The latter featured one of his most famous numbers, "The Rich Kid Rag." It was an example of another trait--Fosse, unsure of himself, always felt safe doing a spoof, and the comedy here was about the rich condescending to a low-class style.

While this was happening, his wife, Verdon, was happily working as his assistant, even though she was one of the biggest names on Broadway. Then she had their daughter Nicole in 1963. Gwen took time off to raise her, but as she was approaching 40, she and Fosse decided it was time for her to do one more big show before she was too old to dance all night. Fosse looked around and finally decided on a musical based on Fellini's Nights Of Cabiria.

The show became Sweet Charity. Fosse tried to write it, as he'd try to write all his shows from now on--there's that attempt at complete control--but it was the one talent he didn't have, to make magic on a blank sheet of paper. He was always filled with ideas, and would happily collaborate, but when it came to going home and typing it up, that was never his specialty. Perhaps this was the reason so many of his best friends--Neil Simon, Herb Gardner, E. L. Doctorow and, above all, Paddy Chayefsky--were writers.

Charity was a hit and Hollywood called again, this time asking Fosse to direct a film version of the musical. It would star Shirley MacLaine (who'd been in the chorus of Pajama Game) because as big as Verdon was on the Great White Way, she was no movie star. Fosse found he loved making movies, and with the help of his cinematographer spent hours and hours shooting from all sorts of angles to see what he could get. In the early 60s, such Broadway adaptations as West Side Story, My Fair Lady and The Sound Of Music were giant hits, so the checkbook was open--which led to a lot of white elephants, including Sweet Charity. The irony was, his fluid stage style made the original show play like a movie, but adapting it to screen made the fun-but-flimsy show seem clunky. Still, this is a large dose of the Fosse style, and many of the numbers look great when watched by themselves.

Fosse licked his wounds and returned to Broadway where he directed another huge hit, Pippin. He fought with the writer and composer over how dark it would be. The final product was maybe the first true Fosse show as we think of him today. Perhaps not deep, but dazzling. With the help of a TV commercial Fosse made--an innovation at the time--the show ran for years.

Meanwhile, he had gotten another movie director gig--some producers are smart, and know the best time to hire talent is after a flop. He was charged with bringing Cabaret to the screen--it was a Harold Prince show that he hadn't worked on (and was probably jealous of--no one took Sweet Charity seriously, like they did Cabaret). He hired Liza Minelli, Michael York and, from the stage show, Joel Grey. But he decided to do something different. The original show had plenty of old-style Broadway numbers, where characters would suddenly start singing. In Fosse's movie, the only numbers would be where the characters were actually singing or performing within the movie.

The movie was a huge hit, and won eight Academy Awards, including best director. That same year, he won two Tonys for Pippin. He also got an Emmy for directing a TV concert Liza With A Z. No one had ever, or likely ever will again, pull off such a hat trick.

So he was in demand on both coasts, and could choose his projects. He decided to make Lenny, a film about Lenny Bruce, and create one last show for wife Verdon (they were separated but remained married), Chicago, based on the 1920s play (which had been turned into a non-musical movie starring Ginger Rogers).

Lenny was a troubled shoot. Fosse now had money and power--enough power to make a drama in black and white--and would shoot scenes over and over. Like Jerome Robbins on West Side Story, Fosse was a perfectionist and a choreographer, and as such was used to working something over and over until he got it right. That approach doesn't work in movies, where every hour costs a ton. On top of that he was working with a big star, Dustin Hoffman, and they didn't get along. Fosse was used to telling his actors exactly what to do, while Hoffman was used to exploring a role and finding the part. Fosse didn't approve--he even told Hoffman not to do any research on his own, even though Lenny Bruce was a well-known public figure.

After all the work, including a long period of editing, Lenny came out in 1974. It didn't make much money, but got a lot of respect, earning six Academy Award nominations, including Best Director. Meanwhile, on Chicago, the same problem as always--Fosse wanted it stripped down and very dark. He fought with Verdon, who had an ironclad contract and saw this as her vehicle. As much as he admired her, even loved her, there was always some jealousy in the relationship--she had the name and fame on Broadway far before he did, and he wanted to prove he was in charge.

Also featuring Chita Rivera and Jerry Orbach, Chicago was a major hit. (A revival twenty years later would become the longest-running revival ever on Broadway). Unfortunately, for Fosse's ego, it was completely overshadowed that season by a musical that opened a week earlier, one of the biggest shows ever on Broadway--A Chorus Line, from his main competitor for King Of Broadway, Michael Bennett.

In the middle of all this activity, something even more significant happened. Fosse had always been a big smoker--in fact, the cigarette on his lip was a trademark. On top of this, he took both amphetamines and barbiturates, prescribed by doctors, to manage his driven lifestyle. He had chest pains and underwent open-heart surgery. If this all sounds familiar, it's because it's the plot of his next film, All That Jazz.

Even before the surgery he'd been working with a screenwriter on a film about a man who dies, but now he decided he could turn it into something autobiographical. (In fact, if you really want to know about Fosse, don't read this book, see All That Jazz.) He helped develop the script, which became about a popular Broadway musical director, uncertain of his talent, also in the middle of editing a movie about a comedian. He has to go to the hospital and the producers start looking to replace him. Also, the musical stars his old wife (played by Leland Palmer, who'd been in Pippin, but here a stand-in for Verdon), while he lives with his new girlfriend, who's a great dancer herself (played by real-life girlfriend and dancer Ann Reinking). He's also got a cute daughter who wants his love.

Playing Fosse is Roy Scheider. Fosse needed a star to get the film made, and after a lot of turndowns hired Richard Dreyfuss, who soon dropped out. Scheider, who can't sing or dance, does a great job. He hung out with Fosse for weeks before shooting to get down his look, his feel, his mannerisms.

The film is done as a musical, but, once again, not a conventional musical. As such, it's probably Fosse's greatest film. It won four Academy Awards as well as the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. But it's also a film created by a man who seems to think he might not mave much longer to live. In fact, the climax is a big musical number in his mind, dreamt during surgery, that precedes his death. How do you top that?

While the film was gestating, he also came up with his latest Broadway show, Dancin'. Nothing but dance numbers from songs he liked. Brilliant, when you think about it. He finally figured out how to get rid of those pesky writers and composers. The show--really a revue--was a hit.

But after All That Jazz, he didn't know where to go next. As it was, he was getting old and tired, and Broadway was moving toward spectacle--Les Miz, Phantom Of The Opera--as was Hollywood, with Lucas and Spielberg. The dark, quirky style of Fosse was a tougher sell.

In film he had enough clout to make something that seemed ruinous, commercially--Star 80. It was based on the Dorothy Stratten story, a Playboy Playmate of the Year who had star potential, but was killed at the age of 20 by her estranged husband Paul Snider. Fosse could actually see himself as the murderer--if he'd been small-time and never went anywhere. Eric Roberts is memorable as the sleazy thug, but the film flopped in 1983 and the critics brought out the knives.

On Broadway he decided to do a show he'd been thinking about for years--a musical adaptation of the Italian film Big Deal On Madonna Street, dealing with small-time crooks and a failed big score. He moved it to Chicago during the Depression and featured African-Americans. Instead of a new score, it featured songs of the period. While Fosse won yet another Tony for choreography, the show, in 1986, was the first flop he'd ever brought into town.

In 1987, he was given some lifetime awards--as if his career were over. Meanwhile, other big names were dying, like Fred Astaire and Michael Bennett (one of many in the Broadway community taken by AIDS). Fosse turned 60, but though he was slowing down, still smoked and took drugs. On September, in Washington, D. C. while overseeing a revival of Sweet Charity, he dropped dead of a heart attack. By that point, it was probably more a question of when.

What he might have done next, we'll never know. But he did leave behind some fine films and shows, and a memorable style still influencing dancers today.

PS. The book has odd chapter titles: "Sixty Years," "Thirty-Seven Years," "Twenty-Four Years" and so on. They're meant to represent how much time he has left. I'm not sure if this was a good idea, but I'll admit it captures the imagination.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home