Nine Tonight

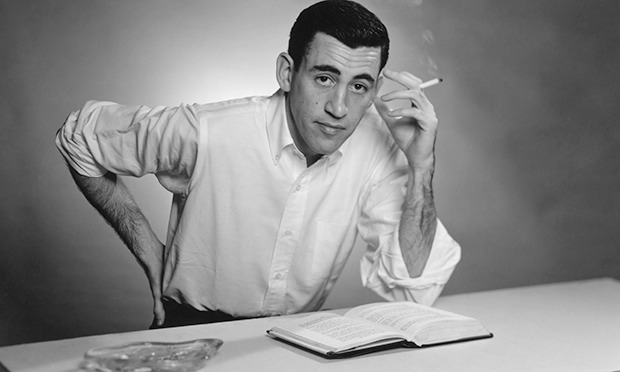

A bit before he became a soldier in World War II, J. D. Salinger was selling stories to magazines. He eventually broke into The New Yorker where he stayed until he stopped publishing altogether. His first book, The Catcher In The Rye, came out in 1951--it was the only novel he'd ever publish, and its protagonist, Holden Caulfield, had previously appeared in his short stories.

His next book, Nine Stories, is, like the title says, nine of his stories. It came out in 1953, featuring work first published in the late 40s and 50s, most of which appeared in The New Yorker. He had plenty of other early work, but Salinger would never allow it to be anthologized.

He'd go on the write more stories, from now on about the Glass family, who'd already appeared in Nine Stories. He published them in book form in two collections that came out in 1961 and 1963. His last published work was in a 1965 edition of The New Yorker. He may have kept writing, but his material, as well as Salinger himself, disappeared from sight. Meanwhile, all his books sold well, led by Catcher In The Rye, one of the biggest-selling novels of all time. (It's easy not to publish when you've got steady royalty checks.)

But let's get back to Nine Stories. I thought I'd read it years ago, but wasn't sure. Anyway, I recently saw it in the library and either read it again or for the first time. In a way, it represents Salinger better than anything else--Catcher In The Rye is an oddity, since he works in short form, and his later work was when he was famous, and could indulge himself. Nine Stories is a mature writer still earning a living.

Like the stories, the book is short--under 200 pages. And they're clearly from an author with a distinctive voice.

For one thing, all the stories are short on plot. Maybe if he were writing for some slick commercial magazine he'd need to have more happen, but he's a stylist at home in The New Yorker, happy to let his characters simply exist, and live at their own pace. His specialty is dialogue. Most of the stories are mainly characters talking, and not apparently doing much. Salinger has a great ear, capturing how people sound, but also how they reveal themselves without trying to. Occasionally he'll use less dialogue, but those stories--"The Laughing Man" and "De Daumier-Smith's Blue Period"--have narrators, so are essentially someone talking to us at length.

Another thing that ties these tales together are a fascination with children, or teens. They appear in almost every story. Salinger was apparently captivated by the young. The stories also tend to feature characters from New York, or at least the Eastern Seaboard, in contemporary settings. (Also, there's a lot of smoking--probably not so noticeable then as today.)

While I wouldn't call the writing comic, the stories often feature humor. It's not quite as incisive as in Catcher In The Rye. Perhaps Salinger had Holden Caulfield's voice down so well he could do anything with it.

I'd say--and many would agree--that the best story is "For Esme--With Love And Squalor." It's almost pointless to describe the plot, since it's all in how Salinger handles the characters and what they say, but it's about an American soldier in England getting ready for D-Day. He has a conversation with a precocious 13-year-old British girl, Esme, in a tearoom. A year later, after having seen a lot of battle, he's cracked up, but is moved by a letter sent him by Esme. Salinger himself saw some of the roughest fighting in the war, so this story may be more personal than much of his early work.

Another one of my favorites is "Just Before The War With The Eskimos." Once again, there's barely a plot--as a teenage girl waits at a girlfriend's house to get some money owed her, she talks to her girlfriend's brother and the brother's acquaintance. That's pretty much it, but the witty and finally moving dialogue carries it along.

The last story, "Teddy," is the most different from the rest and the most troubling regarding Salinger's career. It was the last written, published in The New Yorker in 1953, after Salinger knew about the success of his novel, and points to where his career was going. Teddy is a ten-year-old traveling with his parents and kid sister on a cruise ship back home to America from Great Britain. He's a prodigy, full of religious and philosophical ideas, and was in England to be interviewed by top thinkers. Most of the story is a dialogue between Teddy and an adult on board who wants to talk to him about his view of life.

At this point in his career, Salinger, already into Zen Buddhism, had just discovered the Vedantic religion. It changed his life. Unfortunately, it changed his writing. Teddy is a tough enough character to buy--a boy who's actually a wise old man. Compare this to Esme, a smart and talented young girl who makes charming mistakes trying to sound adult. But Teddy we're meant to take seriously, and the adult he talks to is a stooge who doesn't quite understand. Teddy is less a character than a mouthpiece for Salinger's religious views, and much of the story is close to a straight lecture. "Teddy" has less humor, less wit, less life than anything that precedes it. I like some of Salinger's Glass stuff that was to follow, but he would become more and more self-indulgent. Maybe he stopped publishing at the right time.

1 Comments:

I remember the titles more than the stories. Its always a perfect day for a bananafish

Post a Comment

<< Home