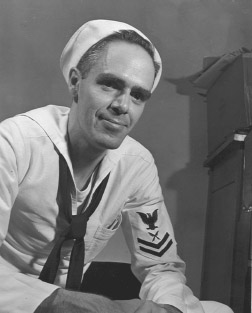

Armand T. Ringer

Just as many would go straight to the sports section of the morning paper, so did millions of readers for over a generation make a beeline for Martin Gardner's "Mathematical Games" in Scientific American. Gardner's column was the most popular part of the magazine, in fact, and Gardner himself a hero to countless nerdy types. And he was a lot more than a columnist, publishing numerous books about science, pseudoscience, magic, puzzles, poetry and philosophy, not to mention his annotations of other writers, such as L. Frank Baum, G. K. Chesterton and Lewis Carroll. (My Annotated Alice has twenty pages printed upside-down--I wonder if that makes it a collector's item?)

He died in 2010 and now, a few years later, comes his autobiography, Undiluted Hocus-Pocus. The text is about 200 short pages, and so whimsically written I have to wonder if it was just notes for something he intended to do more seriously later on. For instance, as short as it is, it's half over by the time he gets out of the navy and truly embarks on his journalistic career.

Worse, most of the book is impersonal--many of the chapters are about people he knew, followed by a description of what they did or thought. The pages, for instance, on his years at the University of Chicago mostly deal with the administrators and professors he met, not what he did there himself. (Gardner often refers to other books he's written if we want more information--I'm glad they're out there, but that's the sort of stuff we want included in the autobiography itself.)

While he follows a general chronology, the book is fairly compartmentalized. His decades at Scientific American, the central activity in his life to many, are dealt with rather quickly in one chapter. And later we get an even shorter chapter on how he met and married his wife.

Only in the last two chapters does he discuss at length his personal philosophy. While Gardner fans may already be aware of these beliefs, this is still some of the most fascinating stuff in the book.

Politically, he was a self-described democratic socialist, which essentially amounts to a big-government liberal. He wanted nothing to do with communism, but seemed more frightened of unfettered capitalism breaking out in the U.S. As far as religion, he called himself a philosophical theist. There was a time early in his life when he was a fundamentalist, but studying science convinced him the Bible could not be taken literally. In later years, he felt that atheists had better arguments and theological assertions were essentially meaningless, but still had a sense of wonder about the universe and believed in all sorts of unproven possibilities if for no other reason than it made him feel good.

Aesthetically, Gardner was a classicist. Not that he didn't like anything new, but much modern art and poetry he thought little of--some of it, in fact, he felt was essentially a scam.

He was also a "mysterian." That is, he believed that there are some subjects, such as, say, free will and consciousness, that we will never truly understand. Just as, say, a dog could never understand quantum physics, so are there great mysteries out there which our DNA precludes us from comprehending. He certainly may be right about that, but I'm not sure where it leaves us--how can we tell what we can and can't understand before the fact?

This may not be the best book on Martin Gardner we could have, but I guess it's the best autobiography we're going to get, and that's good enough for me.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home