On The Roof And Around The World

I doubt there could be a better book on the Fiddler On The Roof phenomenon than Alisa Solomon's Wonder Of Wonders, at least for the first two-thirds, but we'll get to that later.

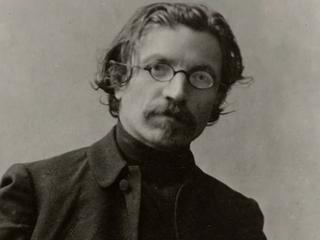

The first of three sections starts where the story must--with Sholem Aleichem. He was a Yiddish author from Eastern Europe at the turn of the last century. He wrote, comedically most of the time, on Jewish themes. His greatest creation was Tevye the Milkman, who'd relate his tales to Sholem Aleichem, telling of his troubles with his five daughters, often misquoting scripture, and slowly gaining self-awareness of what was going on.

Sholem Aleichem (a pen name that, in the Yiddish idiom, means "how do you do"), though popular, often had money problems. He moved to America in the early 1900s, hoping to make some dough in the burgeoning Yiddish theatre. But as beloved as he was, his talent wasn't in drama, and, furthermore, he misjudged the American market: Jews living in New York didn't view life in Russia with nostalgia, they wanted something more forward-looking, so Aleichem's plays didn't make money. When he died in 1916, there were hundreds of thousand of mourners. And, ironically, it was the start of a successful dramatic career.

Yiddish theatre adapted his fiction and it went over big. They were able to emphasize whatever suited them best, making the stories more comedic and melodramatic, in ways that the original author may not have approved. (In fact, Sholem Aleichem could be pretty dark. In one of his later Tevye stories, the milkman's daughter Shprintze kills herself when rejected by her beau's rich family.) It was actually the beginning of a struggle for the meaning of Sholem Aleichem, when the vulgar versus the elite would argue over what was truly "authentic."

His popularity waned somewhat between the wars when Jews were assimilating, but that changed with WWII, when suddenly Jews were far more oppressed than they'd been in czarist Russia.

Two things really brought him into American consciousness. First, in 1943, Maurice Samuel's highly popular English-language collection The World Of Sholom Aleichem. (Yiddish needs to be transliterated, thus the different spellings.) Then in the 50s the play--or actually three one-acts performed as one piece--also titled The World Of Sholom Aleichem. The book was the more sentimental piece, wallowing in old-style Yiddishkeit. The play was created and performed by blacklisted artists, leftists who at the time were looking to celebrate folkways, and maybe saw in the struggles of their forebears something like the struggle they were going through.

Meanwhile, some thought of adapting Sholem Aleichem for Broadway, but it was still a time when Jews were putting their past behind them and becoming Americans. Was shtetl life too Jewish for the Great White Way?

After some false starts, the songwriting team of Bock and Harnick, who'd written the score to the Pulitzer Prize-winning Fiorello!, deciding to take on Tevye. Joined by playwright Joseph Stein they soon were showing their work around--even before they'd secured the rights.

Harold Prince, who'd turn out to be their main producer, didn't like the material. Like the authors (and so many others involved in the musical), he was Jewish, but this wasn't his German-Jewish history and he didn't go for the ethnic stuff. But he thought if brilliant director-choreographer Jerome Robbins liked it, he could get behind it.

Robbins was in great demand, and it was hard to pin him down. But at that moment, he was looking into his roots (he was born Rabinowitz), and realized this could be the vehicle where he would express himself. He got on board, started doing massive amounts of research, and demanded significant changes. For instance, he didn't like the opening number about Tevye's family hurriedly preparing for the Sabbath. He kept demanding to know what the show was truly about. Finally, someone said it's about the breaking down of traditions. Robbins jumped on that and Bock and Harnick wrote the opening number that set up everything that followed: "Tradition."

Robbins also spent half a year casting the show--he wanted people who seemed authentically in character, not stage Jews. Above all, the production wanted the great stage actor Zero Mostel, who had the spirit, the comedy and the size to make the role special.

Mostel had recently become a big name on Broadway after starring in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum. The musical--the first with a complete score by Stephen Sondheim--had been in trouble out of town. They called in show doctor Jerome Robbins, who made it work. The problem had been, though, that Mostel and his co-star Jack Gilford had been blacklisted, while Robbins had been one who named names. But Mostel said the Left didn't blacklist, and worked with Robbins, even if he didn't respect him as a person.

It took a while to pin down Mostel, and even after signing the star and the director remained uneasy with each other. Mostel, loud and demonstrative, would swear and mock, while Robbins, a martinet, would quietly get his way.

The show tried out in Detroit (back in the days when shows did things like that) and later Washington. Though it had problems, and was way too long, it clearly had something. There was an early thumbs down from Variety, but in general the word of mouth was solid.

Robbins was a great procrastinator. He'd work forever on minor scenes and put off major dances for weeks. On the road, a lot had to be cut. For instance, a long dance where Tevye lost his daughter Chava to another religion was very powerful, but too long near the end of the show. Also, a song about when will the Messiah come was cut--much to the consternation of Mostel--because while entertaining it didn't fit. Austin Pendleton, as the hapless tailor Motel, saw a charming song about his sewing machine cut--it never played because it was too late in the show, his story was over and the audience wanted the action to move forward. In fact, Pendleton's other song, "Now I Have Everything," was given to Bert Convy's Perchik. He wondered if he was about to be fired. But then Bock and Harnick wrote "Miracle Of Miracles" (where the title of the book comes from) for Motel and it was a delight.

Robbins was also busy adding new choreography, especially the show-stopping wedding dance. He also wanted a big lively number to start the second act, but after creating a piece with all the citizens of the village joyously turning whatever was nearby into a percussion instrument, he cut it just before the production moved to New York. He and the authors agreed this moment was an excuse for a big number, but if the story demanded something quieter, they'd break the conventions of the musical.

Anyway, the musical was a gigantic hit--the biggest up to that time. It certainly wasn't too "Jewish." In fact, it seemed universal, and played around the world. It also restarted the old controversy, where the cultural gatekeepers, protecting the authenticity of the original, denounced it as kitsch.

In the third section of the book, Solomon looks at the spread of Fiddler through the world, including Israel, where its debut was a cultural event. There's also the Norman Jewison movie. Jewison (a gentile) was a hot director at that point, having recently made The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming, In The Heat Of The Night and The Thomas Crown Affair. However, though Fiddler the film was a big hit, it's not exactly a classic. He wanted something realistic, and downplayed the laughs and other aspects that make musical comedy musical comedy. Perhaps this had to be done, but most feel the film only captures a small amount of what made the live show work.

Unfortunately, Solomon spends a chapter on a high school production in Brooklyn starring African-American kids that became a flashpoint for black/Jewish relations. (She inserts some of her politics, too, which don't really help the book.) She also has a chapter on Fiddler in Poland. Both these chapters, while featuring interesting stories, could have been told in a few pages, as part of a larger tapestry.

But if the final third of the book flags, it's more than made up for by the first two sections.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home