Straight From The Drawing Board

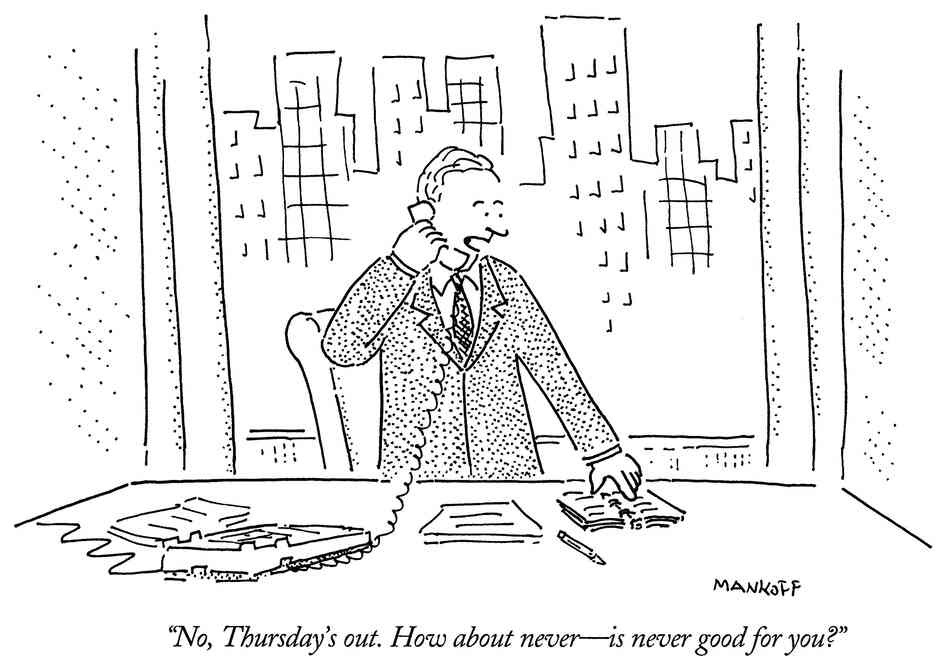

How About Never--Is Never Good For You? isn't a particularly descriptive title for cartoonist Bob Mankoff's new book. More helpful is the subtitle: "My Life In Cartoons." But the title is there to catch the attention of a target audience that recognizes it as one of the most famous captions in any New Yorker cartoon. The full version--showing a businessman on a phone--has him saying "No, Thursday's Out. How about never--is never good for you." It's deservedly a classic and is quoted by many, most probably not aware it came from the pen of Mankoff.

But maybe no single title could envelop this hybrid book. At almost 300 pages, it's an autobiography of Bob Mankoff, a history of New Yorker cartoons, a description of how Mankoff runs today's cartoon department, and a collection of great cartoons.

Mankoff was born and raised in New York, and, with a strong sense of humor and drawing talent, decided to be a cartoonist. This may have been disappointing to his family, but in the late 60s young people were looking to find themselves, and there were still enough magazines out there publishing cartoons that you might make a living at it. He sold his work to places like Saturday Review and National Lampoon, but wanted to get to the top of that world--The New Yorker.

The New Yorker had been publishing humorous illustrations since its start in 1925, putting out material by such names as James Thurber, Peter Arno, Charles Addams, Saul Steinberg and so many others, each with a recognizable technique or approach. Some of the famous cartoons of the early years included a little girl, referring to her broccoli--"I say it's spinach, and I say the hell with it"--and a draftsman walking back from a plane crash stating "Well, back to the old drawing board" (which is where the cliché comes from). The New Yorker style would change with the times, somewhat, but was generally oriented toward the relatable, the subtle, the whimsical, and avoided anything too nasty or gross.

Mankoff felt he needed to distinguish himself, so he started drawing with dots--also known as stippling. A time-consuming approach, but no one else was doing it (maybe because it was so time-consuming). After hundreds of rejections, he sold his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1977. Now that he was in the club, he started getting maybe one cartoon in per month, then two a month, until in 1980 he was offered a regular contract with the magazine. This still meant bringing in ten or fifteen cartoons a week and having most, or all, rejected, but he was in.

At the time, the arts editor, who'd give the thumbs up or down, was Lee Lorenz. When he took over, there were plenty of famous New Yorker cartoonists regularly contributing, but he also developed a new stable of talent for the magazine, such as Mankoff, Mick Stevens, Jack Ziegler, Michael Maslin, Peter Steiner and my personal favorite, Roz Chast.

A bit later you'd get Bruce Eric Kaplan--aka BEK--who'd not only become a New Yorker favorite, but would also write the classic Seinfeld episode mocking New Yorker cartoons, which gets a whole chapter in Mankoff's book.

In 1992 Tina Brown became the magazine's editor and pushed for an edgier style. This discomfited many readers, but even if a little harsher than usual, the cartoons continued to be of high quality. Then in 1997, under Brown, Mankoff was named cartoon editor. Now it was his job to find new names who'd eventually take the place of the oldsters (i.e., Mankoff's generation).

With the steep decline in general magazine sales that continues to this day, soon there was barely a market for cartoonists, so Mankoff tried to develop talent, taking in promising students and teaching them basic comic technique. He also would publish them while they were still a little green to spur them on to greater work. Out of this new generation we get names like Alex Gregory, David Sipress, Drew Dernavich, Matt Diffee, Paul Noth and Amy Hwang.

Mankoff also goes into the process where he and editor David Remnick narrow the thousand or so cartoons sent in each week to the seventeen or so that will make it into each issue. Then there's the story of the weekly caption contest--a popular back-page feature that started on his watch.

The book is written in an informal, jokey manner--not at all like his magazine's style--but then, this guy does cartoons, not multi-part essays on geopolitical issues. Copiously illustrated--as you'd expect--it's a quick read, and a fun one, even if you've never seen a copy of The New Yorker.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home