Freaky

A decade ago economics professor Steven D. Levitt and New York Times journalist Stephen J. Dubner came out with Freakonomics, a surprise bestseller that taught people to look at the world as an economist does. For example, they believed a significant but rarely-discussed factor in America's dropping crime rate was legalizing abortion, which meant many children who would have grown up to be criminals weren't born to begin with.

Some of their claims are controversial, but their basic way of looking at things is a useful antidote to how a lot of policy is discussed. When trying to solve a problem, or deal with a tricky situation, it's worth noting, for instance, that people respond to incentives, or that conventional wisdom needs to be tested like everything else. It may sound obvious, but many people get stuck in certain ways of thinking.

Levitt and Dubner started their own Freakonomics industry, doing consulting work and following up with two more bestsellers, SuperFreakonomics and their latest, Think Like A Freak--which I just read. It's a fairly short book (a little over 200 pages of text) that "offer[s] to retrain your brain." I don't know if it goes that far, but, like their previous work, does suggests helpful ways of looking at things.

What, then, is thinking like a Freak? It's not that hard to describe, though it can be hard to do. First, admit what you don't know. Many people make the same mistakes over and over because they won't admit it, or are afraid to be revealed as ignorant.

Identify what the actual problem is--not what everyone says it is, but what the data show it is, as best you can discover. And try to break down the problem into smaller parts, which are easier to study and easier to solve.

Ask basic questions, as if you know nothing about the situation--come at it fresh. And, while investigating a problem, try to ignore your moral compass (at least short term) since it can get in the way of effective solutions. Also remember that we all hold deep biases--so deep that we're essentially blind to them.

Never forget that people respond to incentives, but also that they'll try to game the system. Try to come up with experiments that can force out into the open how people respond--not just what they say they'll do, but what they'll actually do.

Finally, be ready to quit--don't throw good money after bad.

That's pretty much it. Perhaps not earth-shattering (especially after their first two books), but, if followed, revolutionary. In any case, the fun part of their books--the reason they sell--are the stories they tell.

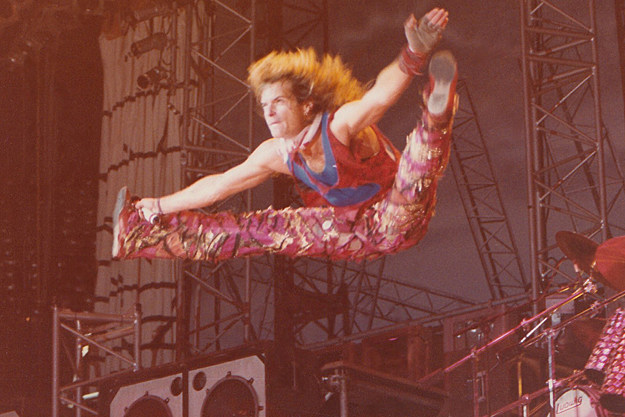

For example, they explain how a young, slight Japanese man revolutionized the world of eating competitions by experimenting with different ways of swallowing a hot dog rather than shoveling it down as everyone else had been doing. Or how one medical researcher overturned decades of thinking on what causes ulcers by simply doing some basic research (which took a while to be accepted, as most challenges to conventional wisdom are). Or how a philanthropist figured out that a great way to appeal to potential donors is to promise to stop bothering them with appeals once they pay. Or how a crazy rider in a rock group's contract (no brown M&Ms) wasn't so crazy, but was designed to ensure the concert promoter was paying attention.

The book is easy to read--a key to their success--though I find the style (which I'm guessing is mostly Dubner's) a bit too folksy at times. The ideas won't be much of a surprise if you've read their previous work, but it's still a reminder that we can take certain things for granted, and need to try a different approach now and then.

8 Comments:

The marketing was over the top (but I assume there are very good freakanomic reasons for indulging in that) but the books boil down to examining your assumptions and looking to identify assumptions you didn't even realize you had. And look at the goal desired to be achieved - a lot of strategies for realizing that are not necessarily satisfying. (i.e - to negotiate a good deal- maybe you should start with outrageous terms and then spend all of time during the negotiations giving in- at the end you feel like a spineless wuss who's been beat but the ultimate deal is often better than if you had attempted a reasonable first offer- the other side gets overconfident in their victories and forget stuff- Don't know why freakanomics made me think of that specifically but it seemed apt- also it only works if they don't figure your game)

Usually it's a bad strategy to start with outrageous terms in a negotiation. If you demand things that the other side knows it will never give you, they'll either believe you're not negotiating in good faith or just think you're not realistic (or think you're a jerk). They'll be less willing to give in at that point.

Imagine you're negotiating for a salary. Let's say the last guy in the position was paid $60,000. If you ask for $75,000 that might be a little more than they're willing to pay, but you'll meet somewhere in the middle. But if you say you want $500,000, figuring they'll be happy when you "settle" for $100,000, more likely they'll just show you the door.

The strategy works better for complicated negotiations with many terms.

Any strategy that assumes haggling will take place doesn't work with me. If I say I won't pay the list price and start to walk away, I hate it when the salesperson says "well, I have authority to grant a 10% discount." That means to me that they were willing to rip me off for 10% of the price, and probably more.

I recently went through this with my Mom's nuring home. They raised prices 11% atthe beginning of this year. I was not immediately offended - health care costs are going up and my Mom requires specialized care. Then some of the residents started leaving (there were other reasons besides price that might have motivated a few departures). Then I heard that if you told the company you were thinking of leaving, they offered you a discount from the new 2016 pricing. They didn't offer us the discount, I only happened to hear about it, and that was it, we were outta there.

The negotiating strategy I respond to is a reasoned explanation of why the object of purchase is worth what they are asking (either how much it costs to make, or how much it is worth once it is mine). I haven't read Art of the Deal, but I am sure Donald Trump could not sell me anything.

So you're not voting for Trump?

Anyway, haggling is built into the system in a lot of cases, as unpleasant as it can be. I have satellite radio and every year they send me a renewal notice for the "full" price, even though I make it clear that I will only pay the original "discounted" price or nothing at all. It makes sense for them to send out all renewal notices automatically at full price, seeing who will bite, figuring few will simply quit. (And we're both in an excellent position to renegotiate. I'm willing to walk away--I don't need satellite radio so will only pay a nominal sum--and it costs them almost nothing to add me to their list of subscribers.)

But haggling, if that's what you want to call it, is often how things work. Imagine you apply for a job--they may ask for your salary requirements. Or put in a bid to get a contract. You have to decide what to ask for, and that's haggling. Most people will not ask for the bare minimum they think they'll need unless they're very frightened they won't get the job. Instead, you tend to ask for the highest you think you can get away with, and then are very likely to come down if there's a counter.

Denver Guy must hate it when a store has a sale. It means he can never go back there.

I come to terms with the real world, but avoid price negotiations as much as possible. I never go to the big sales days (holiday weekends, the Friday after Thanksgiving, etc. Once in a while, if I see an advertised sale price, I have clipped it and taken it with me after the sale and asked them to match the price that was good the week before. I got a car that way a couple decades ago (it was the loss leader ad, and after the sale, they still had that car, and they tried to get me to bu a more expensive one, but like LA Guy, I was willing to walk away so they gave it to me. But that means everyone who came to shop on the sale day either walked away or bought something more expensive, so I can see why they do it.

I prefer silent bids - everyone bids what an item is worth to them, and even if that's more than the seller would have been willing to take, I got a fair deal. I have liked using Priceline this way for hotel and plane reservations.

It would be fun to know, as you walk on a plane, what everyone paid for their seats. They're all pretty much the same (in coach), but the costs vary widely.

Post a Comment

<< Home