Not Just For Laughs

I just read Why Comics? by Hillary Chute. While it nods to older, more conventional formats, it's mostly about underground comics and graphic novels.

The book looks into various subjects comic artists take on, chapter by chapter, such as sex, superheroes, war and the suburbs. It's a physically heavy book, by the way, since it's printed on shiny, high-quality paper--presumably to ensure the many reproductions are given their due.

The chapters generally concentrate on a few big names. They're the usual suspects: Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Matt Groening, Lynda Barry, Harvey Pekar, Gary Panter, Chris Ware, Charles Burns, Alison Bechdel, Jaime Hernandez, Marjane Satrapi and so on.

The book, written in a no-nonsense style, takes comics seriously. A few decades ago, very few did, but now comics are taught in colleges, and artwork from comic artists appears in museums.

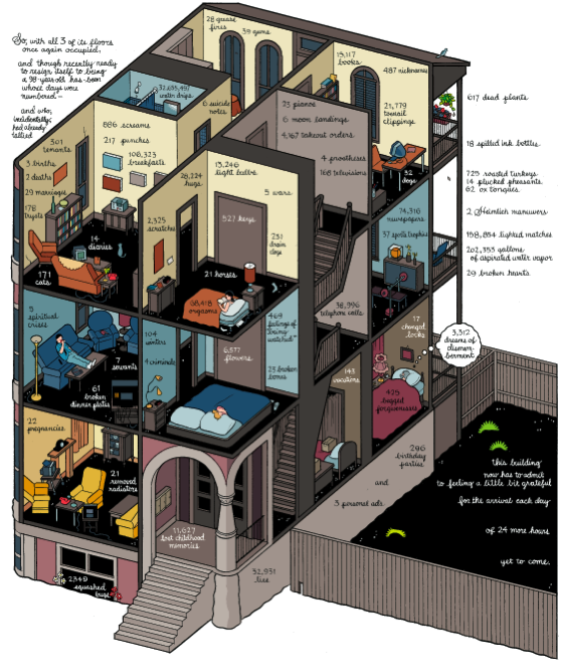

It makes sense. Comics can take on anything--personal, political, humorous, tragic--and handle the subject as no other art form can. Both the verbal and the visual matter, as does how they mix--sometimes they complement each other, but sometimes they clash.

Comics have their own code, too, much of which we take for granted. For instance, we understand a word balloon, and wouldn't confuse it with a thought balloon. And storytelling techniques are different from other formats, as panels exist in time and place, but often it's what's in-between them that matters most.

As the book demonstrates, all great comic artists have their own style, whether it's heavily shaded or in vibrant color, precisely drawn or intentionally sloppy. Some tell stories in a simple, straightforward manner, while others require close reading. Some have so many words you can barely see the characters, while others use only pictures.

I wouldn't say comics have the respectability of something like novels just yet. The question is will they last. If, in a hundred years from now, today's top names are still being read, they'll have passed the test.

3 Comments:

Interesting. I just read bits on Amazon. The author argues against those fans who shun the name "comics" -- as in "Comics are for kids, I read graphic novels!" But aside from her terminological preference, she clearly thinks that the vast majority of comics are beneath her notice.

By far the most common kind of comics are superhero comics (using the word in the broad sense to include all powered heroes and costumed vigilantes). This genre gets one chapter in her book. (And DC as "the staid sister of Marvel" hasn't been true since the Silver Age). From 1935 to 1980, there were also vast quantities of Western comics (Indians being often, but not always, the badguys), war comics, romance comics, and humor comics -- and these don't seem worthy of mention at all.

Within a minute I found an error (she claims that the name "DC" is taken "from the original Detective Comics issue that featured Batman's debut" -- false, as the name predates Batman by two years.

I went through the chapter on superheroes, and (although the Amazon excerpt omits some pages) it appears that the author's focus is on superhero comics that deconstruct the genre's traditions. She mentions the trop of DC being "the staid sister of Marvel" and suggests there are a couple exceptions to this rule -- but in actuality this rule was only true in the Silver Age.

I could just be nitpicking. But my approach to a nonfiction book is to look up the things that I know about first. If the author makes errors in those parts of the book that I am able to verify, why should I trust her claims in those parts of the book that cover material I am unfamiliar with?

I guess we should expect her to know all about comics, no matter what the genre, though clearly certain types of comics interest her more than others.

As someone who's noted quite a few errors in books over the year, one thing I've noted is they often occur when the author is writing a bit beyond the subject at hand. The author may have done a ton of research on the main subject, but will often rely on questionable material or just vague general knowledge to note something that's tangential. Sounds like this author just wasn't interested in other types of comics enough to get it right, though what it says about the reliability of her main material I can't say.

Your comments about the author's reliability make sense.

"Trendy" books that deal with mainstream comics tend to focus on the political topics: Superman's early exploits were sometimes "social justice" missions; Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams' Green Lantern / Green Arrow series dealt with big social topics circa 1970 (racism, exploitative capitalism, overpopulation, drugs); many Golden Age writers and artists were Jewish and brought a minority perspective; post-1980 comics have featured LGBT characters; etc.

These are important topics to be sure, but it's like the folks who say that Star Trek was great because it had TV's first interracial kiss, and an anti-racism episode. That may be true, but you'd be hard pressed to find a Star Trek fan who watched the show because of that, and all the social justice moments only make up a tiny fraction of Star Trek -- or traditional comic books.

If I were writing a book about the unique place of mainstream comic books as art, I would focus on the following:

1. Each new writer and artist puts their own spin on an existing character. This is something that mainstream comic fans care about a lot. "John Byrne, famous for his work on X-Men, is now going to write Wonder Woman. How will he approach this character?" That question is constantly being asked by fans: When Frank Miller writes Batman, or Straczynski writes Spider-Man, or Grant Morrison writes the JLA, they will put their own spin on the book, but they aren't free to ignore everything that has come before. (I think this is analogous to how classic rock and blues songs were covered by dozens of artists, each producing something the same and yet different.)

2. The longevity of characters that the fans follow allows very gradual growth and development. Peter Parker deals with death in the family, graduates high school, gets engaged, sees his fiancee murdered, falls in love with someone else. Robin (Dick Grayson) graduates high school, tries to get Batman to accept him as a peer instead of a junior partner, eventually rejects his role as Robin and takes on a new identity (Nightwing) on his own, and then when Bruce Wayne is crippled Grayson must return to Gotham City to help him. If these were done as novels or movies they would happen quickly. But these sagas actually developed over forty years of very slow character development. No other medium allows this kind of very slow, incremental character growth that moves almost at a real-life pace. (The closest analogy is TV shows with young actors like Gilmore Girls or Buffy, but there the writers are constrained to let the characters age at the same speed as the actors, whereas in comics there is more flexibility.)

Post a Comment

<< Home