All That Jazz

Moving To Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life is most interesting as a look into the mind of Wynton Marsalis. He's a man who's trying to defend a music that most people feel is only worth hearing at a museum or in the context of nostalgia.

Making it even tougher, Marsalis has to defend jazz from above and below. The threat from below is modern pop music, which has usurped the central role jazz once played in American life. The temptation of so many jazz artists is to just give in and play what the public wants, rather than do their best and hope the public comes to them. The threat from above was there at the beginning, when jazz was seen as a lower form of music. Since then, many jazz artists have longed for the respectability that serious music originating in Europe has. Worse, according to Marsalis, many jazz artists have fallen under the sway of the atonal siren song of 20th century musical theory, which believes in throwing out musical traditions; formerly, jazz would build on its past, and not forget its roots in the blues, but now too many simply get esoteric for its own sake.

Marsalis himself has gone on a personal journey, taking years to fully appreciate the music he now proselytizes for. In his best chapter, he talks about what different jazz greats have added, and in his essay on Louis Armstrong, he notes it's best he never met him as a child, since he didn't want the opportunity to even think "disrespectful thoughts in the presence of such a great man."

he notes it's best he never met him as a child, since he didn't want the opportunity to even think "disrespectful thoughts in the presence of such a great man."

he notes it's best he never met him as a child, since he didn't want the opportunity to even think "disrespectful thoughts in the presence of such a great man."

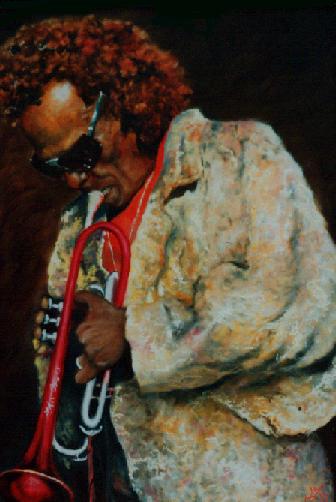

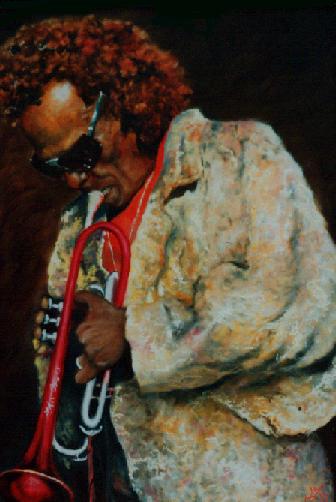

he notes it's best he never met him as a child, since he didn't want the opportunity to even think "disrespectful thoughts in the presence of such a great man."His most telling essay is on Miles Davis. Davis had a lot of talent, but also had certain limits as a musician. Through years of hard work and a sense of artistic integrity, he was able to create some of the most significant jazz ever. But then, later in life, he sold out (at least Marsalis feels so). Davis wanted to make money and he wanted to be with it, so he moved into the rock world. He got plaudits from rock critics, but stopped being an innovator. He's gone now, but his great jazz lives on, while his bad rock (according to Marsalis, and I agree) is forgotten.

I think that's what I like best about Marsalis, even if I may not agree with him on a lot of things. This book may have a message that jazz is for everyone, but that doesn't mean he thinks just any jazz is okay. He's not simply an evangelist spreading the good news, he's also a harsh taskmaster, who supports the desire to listen to or play jazz, but believes it's your duty to live up to the music.

3 Comments:

The problem with proseltizing art is, in the end, you cannot talk people into liking something. Particularly if we are talking about entertainment, if you have to explain why something is good, you have already lost the battle.

You've noted that in all likelihood, the music of the Beatles will still be played 500 years from now - because it is fundamentally entertaining and someone who knows nothing about rock music will generally enjoy.

The same can be seen in classical music. During his life, Mozart was not that popular, and the elder Salieri was immensely popular. Today, because Mozart's music is fundamentally entertaining, it lives on. Afficionados and musicians may know and listen to Salieri (and any number of other less entertaining composers, but there will be fewer and fewer of them to champion such music as 500 years rolls by.

Now I enjoy some jazz music, but 500 years from now, I imagine it will be the most entertaining pieces that are still listened to (like Louis Armstrong, Duke Elington, and probably the Vince Guaraldi Trio, as long as Charlie Brown cartoons are considered entertaining).

I don't recall saying the Beatles will still be played in 500 years, but I guess I think there's a good chance of that. (I know I have said they should be played in 500 years.)

I've written about the test of time before--even if we don't like it (and I'm not thrilled about it), it's the only test we have that will judge the value of art in the long run.

While his stature only grew after his death, Mozart was fairly popular in his day. A better example of someone who wasn't that recognized as a composer while alive is Bach.

The problems with the test of time are that it necessarily leaves so much out and that it relies a lot on luck as much as enduring entertainment value.

Post a Comment

<< Home