Yes They Said Yes They Will Yes

When I picked up The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle For James Joyce's Ulysses, I feared it would be rough going (like the novel itself). Written by academic Kevin Birmingham, and with over fifty pages of notes, it could easily have been a dry exercise. It turned out to be one of the most compelling stories I've read in a while.

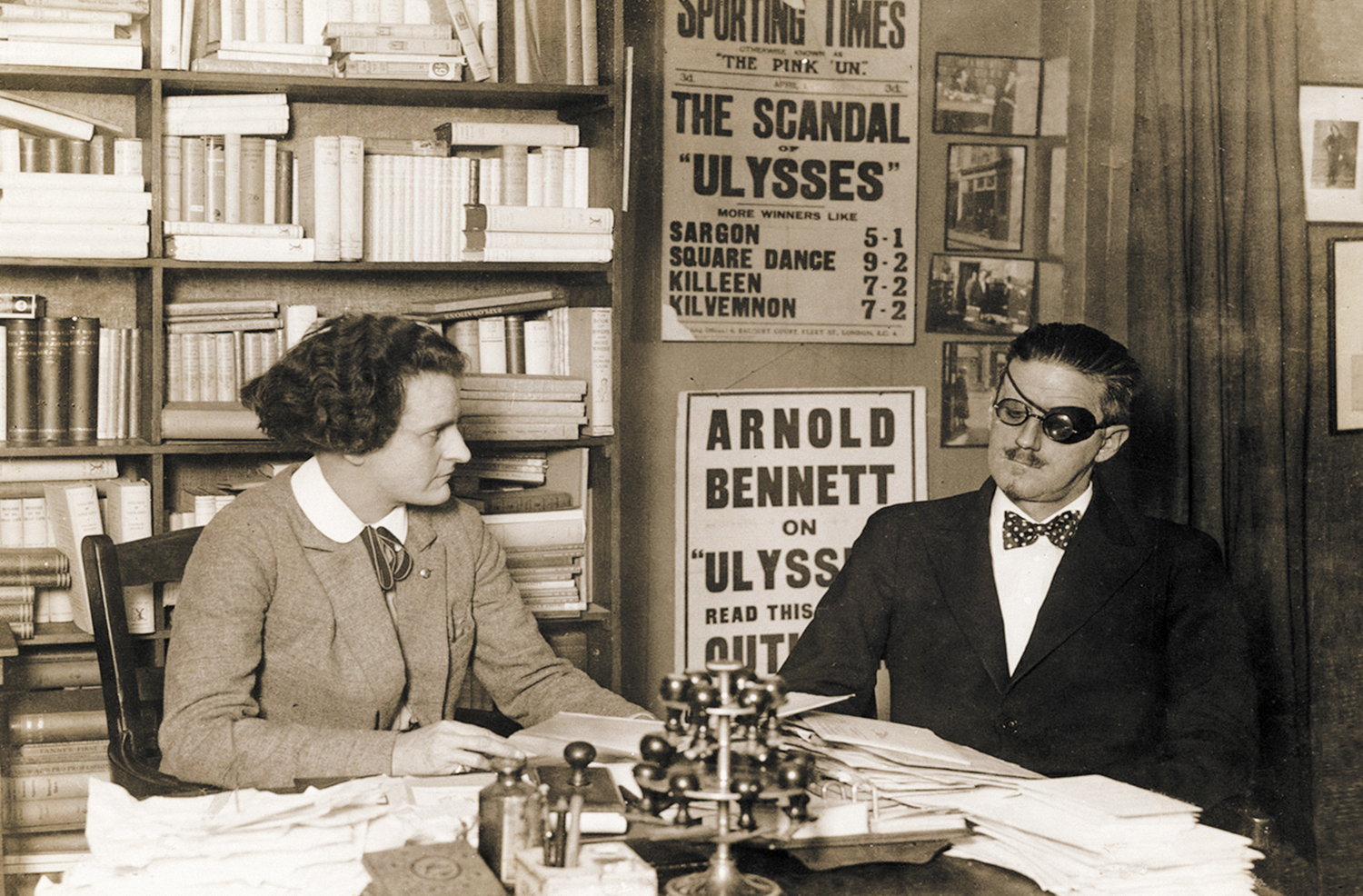

At the center, as you'd expect, is Joyce himself. Leaving Dublin in the early 1900s, he lived, with his wife and family, in Trieste, Zurich (during WWI) and Paris. He was a true artist, not just in his output, but in his commitment. He wrote what he wanted how he wanted, and nothing was going to get in his way. One of the biggest obstacles, we discover, was terrible eye pain, mostly caused by iritis, itself caused by syphilis (in an age without penicillin). He would sometimes collapse from the pain, and required numerous surgeries over the years.

It was a time of revolution--in politics and the arts--and there was a small but growing group of people who recognized Joyce, with Dubliners and then The Portrait Of An Artist As A Young Man, as the voice of modernism. This is the group that helped sustain him through the years of Ulysses.

Among them were patrons who sent money to keep him going. Not that Joyce always appreciated it, artist that he was. In fact, he could be a bit of a spendthrift, going out on sprees, and then ask them for more. (Through the years he received the equivalent of over a million dollars).

Then there were the small booksellers and magazine publishers who encouraged him and sold his work. And when no one could find a printer for his "obscene" work, they were the ones who stepped forward.

As it must, Birmingham's book spends a lot of time with the censors, both American and British. It was a different time, when being called a censor was no insult--indeed, these people, dedicated to suppressing vice, happily attended book burnings, proud of their service to the public.

Ulysses, a massive work that tries to encompass all of humanity into one day in Dublin, was published in 1922. The novel caused a sensation, declared a masterpiece by some, the vilest piece of filth by others. (And, working its magic, some who only saw the pornography at first would come around.) Whereas previously authors drew a curtain on certain parts of life, Joyce felt he had to include it all, and that was the problem. Indeed, even before the book was published, excerpts that appeared in magazines had been declared obscene in America.

Published in Paris by one of Joyce's patrons who had no experience with such things, it was smuggled into America by the thousands. There was strong demand--at least by the standards of a challenging modernist work. Anybody who was anyone had to have a copy, even though (because?) it was contraband. Many copies were intercepted at the border, of course, and the burning began. (If it was printed in America, they would also have taken the plates and destroyed them.)

The threat of censorship was no joke. It didn't just mean the book wasn't easily available. It meant anyone who published, distributed or sold it could spend years in prison. And the censors didn't even stop there, but fought to prevent even public discussion of the book on the radio or in university lectures.

But the world was changing. There had been much repression during and after World War I in America, with a major red scare and laws to back it up. In fact, this was the era when, for the first time, the Supreme Court started hearing cases about the freedom of speech clause of the First Amendment. Before then, it had essentially existed only as a federal warning about prior restraint. But even under new interpretations, it was thought to only cover political speech. No one believed pornography or blasphemy were protected.

Even without a First Amendment argument, though, the idea of what is obscene and what isn't was being challenged. Whereas the older test was simply (and arbitrarily) anything a judge might think would lead to the corruption of the weakest-minded reader, some now thought a better standard would take into account the literary value of a work. It took years, but finally in 1933 a judge declared it legal to publish Ulysses in the United State, and Great Britain soon followed.

Even after its revolutionary changes have been absorbed into the mainstream, Ulysses still holds its power. It's also sold millions of copies. Joyce would go on to complete one more major work, Finnegans Wake, even more complex (and less popular) than Ulysses, before dying at 58.

A pretty exciting story, with many colorful characters. I wonder if it'll be turned into a movie?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home