Wild About Harry?

I just read Gabriella Oldham and Mabel Langdon's Harry Langdon: King Of Silent Comedy. The subtitle is a bit much. Langdon may be the "fourth genius" of silent comedy, after Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd, but in comparison to those masters his inspiration is spotty and his achievements lesser.

Still, with so many books out there about the big three, it's good to finally hear Langdon's story. I've seen some of his shorts and his better-known features, but not much else. The book helped fill in the gaps.

He was raised in Council Bluffs, Iowa in the late 19th century. He could have joined the family painting business, but instead left home as a teenager to join the medicine show. He had always loved show biz and developed a vaudeville act and persona. In particular, he toured in his routine "Johnny's New Car" for many years in the early 1900s (when the automobile was still relatively new).

The act had Harry traveling with his girlfriend (and sometimes others) when his jalopy breaks down. The laughs came when his hapless character tried to fix it, only making things worse.

The act went through variations, but he played it for almost twenty years before Hollywood signed him in 1923. No one was sure what to do with him, but he eventually started making shorts for Mack Sennett and became a popular comedian. By this point, Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton were well established, and doing features.

He took a while to adapt to the movies, and had the help of a team of writers and directors, including an up-and-comer named Frank Capra. Capra would later claim it was the team that figured out what Langdon should do on screen, but this is an exaggeration, since Harry had been a solid star on stage for over a generation at this point. (Though he made it in films after the other great clowns, he was actually older than they were.)

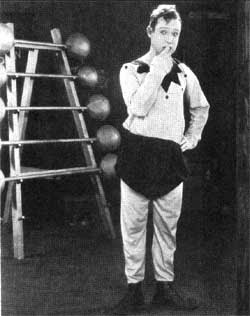

Langdon was an original. He played, essentially, a child in a man's body. Whereas the other great clowns were generally fast, he was usually slow. And while they could be quite efficient and even ruthless in getting things done, Langdon's specialty was being unaware and ineffectual. If things worked out for him, it was often by luck. Critics saw something different, and special, in Langdon. Many welcomed him as the greatest new clown since Chaplin.

In a few years he made the leap to features (against Sennett's wishes), making his three most famous full-length productions--Tramp Tramp Tramp, The Strong Man and Long Pants--in 1926 and 1927. At that point, he fired Capra, who had directed the last two. Capra claims all the comparisons to Chaplin went to his head and Langdon figured he could do everything himself.

This isn't entirely false, though Capra was bitter about what happened--and harmed Langdon by spreading the message around Hollywood that he was impossible to work with. It is true that Langdon went downhill when he was in complete control of his films, and never recaptured his popularity. Then sound came in, which was another blow.

This is when I mostly lose track of his career, but much of the book is about the work he did after the silent era. Turns out he did plenty, both on stage and onscreen. He was no longer the name he'd been, and he did work in cheaper productions, for less money, often in smaller parts, but he didn't give up.

In fact, as the IMDb shows, he appeared in around 60 films (mostly shorts) in the 30s and 40s, before dying of a heart attack at age 60 in 1944.

There was some rediscovery of his work in later years, but so far, he's never enjoyed anything near the revival of someone like Keaton.

I haven't seen his films in years. I remember liking him at his best, but not thinking he was on the same level as his greatest contemporaries. The book has convinced me to give him a second chance. Though I wish I could see him on the big screen with an audience, since that's the truest and fairest test.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home