Moral Measure

Skimmed through Sam Harris's book The Moral Landscape in the library. Harris is part of the "New Atheist" movement and has written previously about why the religions of the world don't make a good basis for morality. His new book goes a step further and states we can use science and other fact-based disciplines to help get objective answers about morality. Since I haven't read the book, I can't say how successful he is, but Hume's argument that you can't go from is to ought is tough to overcome.

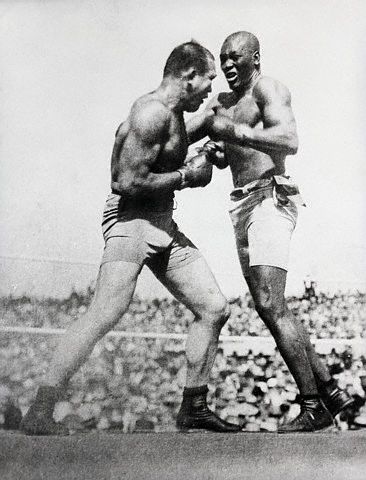

I did read a bit where he says says he believes we've made moral progress in the last century. One example he gives is how much less racism there is in America. He quotes the astounding (by today's standards) LA Times "A Word To The Black Man" editoral of 1910, written after African-American Jack Johnson beat the white James Jeffries for the heavyweight boxing championship:

A word to the black man

Do not point your nose too high

Do not swell your chest too much

Do not boast too loudly

Do not be puffed up

Let not your ambition be inordinate

Or take a wrong direction

Remember you have done nothing at all

You are just the same member of society you were last week

You are on no higher plane

Deserve no new consideration

And will get none

No man will think a bit higher of you

Because your complexion is the same

Of that of the victor at Reno

There's no doubt racism has been discredited since then, and almost everyone thinks this represents moral progress. I sure do. But as strongly as we may feel, isn't it begging the question?

We decide what morality is. We decided (through experience, greater empathy, and a better understanding of genetics, I suppose Harris would note) that racism is wrong. So now we look at former morality and say we're better than we used to be. But wouldn't we say that no matter what direction our morality moved? If fascism had won the day, might we not say that we have a higher morality than we used to--we've purified society and now support stronger allegiance to the state that makes us all strong, healthy and decent?

Maybe Harris can answer this, but I think he's got his work cut out for him.

9 Comments:

Morality is a human construct, no doubt. If religion is a human construct as well, then they are simply part and parcel of the same human desire to find guidance for our free will (which replaced the instincts that all other animals rely on). An argument can be made that scientifically, humanity needs morality to succeed as a species, so our morality is part evolution.

But it is quite a stretch, in my opinion, at least as long as there is no evidence that humans operate subconsciously as a collective. Ants and bees, for example, demonstrate self-sacrifice for the greater good, but these actions are strongly driven by hard-wired instincts and chemical triggers that are the product of millions of years of evolution. I don't think these kind of explanations wash for human altruism, where it is seen.

The evidence of a moral sense developing through evolutionary channels isn't hard to explain. In fact, human altruism--both through natural genetic altruism toward relatives that's seen everywhere, and in successful strategies that work in any large society--developing through biological means stands on pretty solid ground. I don't think this is what Harris is arguing about (though maybe I should just read the book to be sure). He's talking about consciously developing a particular morality (though perhaps not a single morality that fits everyone at all times) based on what we know and can learn--as opposed to moralities based on ancient scriptures or other religious concepts which he feels don't serve us as well.

By the way, your first sentence, "Morality is a human construct, no doubt." I think there is a lot of doubt and, in fact, that's precisely what Harris is fighting against.

Its dangerous to argue these points without having read the book (but when has that stopped us before). If morality is not a human construct, then what is it? An innate way that everything ought to be?

Racism seems as naturally abhorrent to people today as perhaps racial mixing or religious mixing seemed to others not that long ago.

Violence has had a similar history- what is unthinkable now and then and to them and us are often polar opposites.

Maybe the issue isn't that there is an innate morality but an evolved adaption to follow a system of morality (whatever its precepts) and that a society or large group moving forward a=on a general sense of agreed rules is more important than the actual rules themselves (or maybe those groups that adapted to poor moral rules just died off)

Then again, I haven't read the book or thought about this until I just read the post, so maybe these are easy ones that Sam takes down in his introduction

What I mean by "human construct" is that without humans, there is no morality. There is no "right" and "wrong" for any other living creatures. Humans may judge a cat playing with a mouse before it eats it as cruel (wrong), but it isn't by any objective standard relevant to the cat. If humans did not exist, there would be no morality - no moral questions or evaluations. Everything alive would simply do what it does.

So the question is, why is morality relevant to humans. Now, if you believe in a higher authority, an overarching purpose for mankind established by some supernatural force, that is one explanation. The alternative I see is morality is a highly refined version of what applies to all animals - instincts.

Sure, we have an instinct to care for our children. Is this a heightened version of ants having an instinct to sacrifice themselves for the good of the colony? Perhaps. The stretch I find is in suggesting human altruism that extends beyond the immediate promotion of one's own DNA is somehow an evolutionary development. But even if it is scientifically explainable, this explanation diminishes morality to simply very complicated instinctual behavior.

What I mean by "human construct" is that without humans, there is no morality. There is no "right" and "wrong" for any other living creatures. Humans may judge a cat playing with a mouse before it eats it as cruel (wrong), but it isn't by any objective standard relevant to the cat. If humans did not exist, there would be no morality - no moral questions or evaluations. Everything alive would simply do what it does.

So the question is, why is morality relevant to humans. Now, if you believe in a higher authority, an overarching purpose for mankind established by some supernatural force, that is one explanation. The alternative I see is morality is a highly refined version of what applies to all animals - instincts.

Sure, we have an instinct to care for our children. Is this a heightened version of ants having an instinct to sacrifice themselves for the good of the colony? Perhaps. The stretch I find is in suggesting human altruism that extends beyond the immediate promotion of one's own DNA is somehow an evolutionary development. But even if it is scientifically explainable, this explanation diminishes morality to simply very complicated instinctual behavior.

I think all this discussion is not what Harris's book is about.

It seems very possible that human's have an inborn sense of morality. Basic ideas like someone who wrongs you deserves to be treated worse than someone who helps you. Or that what's yours is yours and no one should take it. (There are certain genetically different people who may not have this sense, and we call them sociopaths. There's also a tremendous--and once again inborn--sense of self-justification, so people will disagree on who is wronged and who owns what.)

There also seem to be concepts like in-groups, clan or others close to you whom you treat differently from outsiders. If we have an innate sense of this, it's not hard to understand how racism and xenophobia can develop.

But humans have a "higher" brain, if you will, that allows for reflection, and even allows us to go against our nature. Or another way to look at it is we have a certain sense of things, but our "nature" is flexible enough to go beyond that. Thus we get lots of individual variation, but also whole cultures that seem to have very different values from others.

Harris, I think, is arguing that we may start with our nature, and our natural sense of morality, but we go beyond that. Religions do this, but so does everyone, even if not religious, so that's not the issue. The question is what morality to follow, and how to develop it. He's already satisfied himself that (and built his career on) religion not being a successful answer to that question. Now he's trying to argue how we should develop that morality.

"Or that what's yours is yours and no one should take it."

or not.

There is an equally inborn sense that everything is for everyone

Last Anonymous

Have you ever had a child? They do not have an inborn sense that everything is for everyone, and I seriously doubt that, without education, they would develop that sense. heck, people easily slip into the notion that other people belong to them, let alone things.

Post a Comment

<< Home