Wilde Times

Making Oscar Wilde gives us a new view of the playwright. This scholarly work from Oxford professor Michele Mendelssohn uses research of unexplored material to show us how Wilde acquired his reputation. We sometimes think that as a young man he arrived in London full blown, but the figure we know him as--witty, accomplished--took some making.

Most of Mendelssohn's book deals with Wilde's 1882 speaking tour of America. He came to these shores with a minor reputation and skills not yet honed, and left with enough knowledge and experience to prepare him for his major work.

Wilde, a brilliant student at Oxford from a notable Irish family, moved to London after college seeking fame, or at least notoriety. He published some poetry and criticism, but was not considered a significant writer. However, he became known--and satirized--as a leading figure in the aesthetic movement. Actually, the movement, as symbolized by art critic John Ruskin, had been around for decades, and was, if anything, dying out. But because the popular press saw fit to mock it, it was riding high in the popular imagination.

In fact, a number of plays using old plots but adding parodies of aesthetes became popular. The biggest of all was Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience. It was presented by Richard D'Oyly Carte, and when Carte sent a company to America, he also sent Wilde as an actual representative of the aesthetic type. Even if Wilde's lecture tour didn't make money, it would be a loss leader bringing attention to the movement and creating buzz for the comic opera.

Wilde, though witty in conversation, was not yet an accomplished public speaker. When he get to America he put together a lecture on the "English renaissance" that was scholarly and dry. But the manager of his tour was a bit of a huckster, and had Wilde do things such as attend a performance of Patience and make loud comments. This got tongues wagging and Wilde's first appearance in New York was sold out.

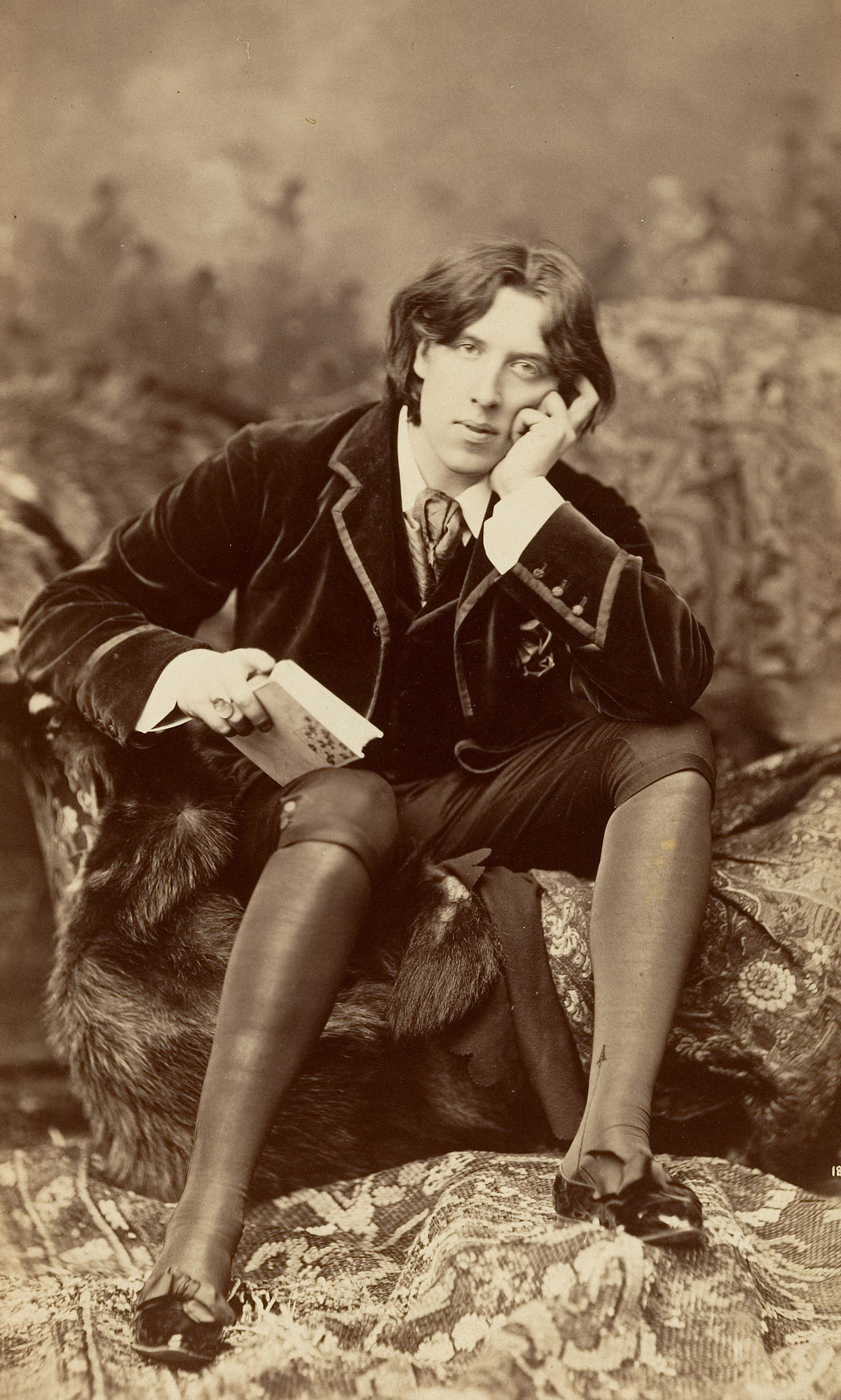

Wilde was also regularly interviewed by the press, and as a good talker got a lot of attention. Mendelssohn notes that 95% of all interviews he ever did were during his year in America. He also had some photos taken in a New York studio, and they became quite well known. Countless copies were traded in America as well as England, and still show up to this day in books and essays about Wilde. (The three photos in this post come from that session.)

Wilde's speeches became fashionable on the East Coast, but he wasn't much of a performer. A few decades earlier, Dickens had wowed American audiences when he acted out scenes from his books, and the public expected to be entertained. As Wilde traveled all over America, as well as Canada, he responded to audience preference, creating a new lecture on "the home beautiful" that, if still meant to be taken seriously, was less abstract and more about practical applications of aesthetic principles.

Wilde also scored a coup when, speaking in Boston, twenty Harvard students mocked him, dressing up ostentatiously as Wildean Aesthetes in knee breeches and silk stockings, carrying sunflowers. Wilde himself appeared in evening clothes and treated them with good humor, mildly scolding them. It turns out this was all planned--yet another publicity stunt--but it got many on Wilde's side, protesting America was not so coarse and rude as these students made it seem.

But Mendelssohn goes deeper into Wilde's reputation. He tended to get negative press, as any representative of a newfangled movement that appears silly to the establishment would. But the point is this previously minor figure was a sensation. There was a hit song written about him, women swooned over him (he was years from having a homosexual reputation--indeed, years from homosexual acts), he was burlesqued on stage in popular new shows.

Also, and this is where Mendelssohn uncovers much new material, there was often a racial tinge to the criticism. In an age of white supremacy--it was assumed by most Americans and Europeans that whites were superior to other races and ethnicities--he was often likened to African-Americans, and the parodies included black figures looking or sounding like Wilde. There were even minstrel shows based on Wilde's character--don't forget the minstrel form was the most popular type of entertainment in America in the late 1800s.

Part of this was related to Wilde's Irish background. Wilde was raised in Dublin, but spoke with an English accent and lived as a British citizen in London. Still, it was a time when Ireland was fighting England over Home Rule, and the Irish were openly defamed as a lower race. In America, many Irish had done well for themselves, but, by and large, were treated with more contempt than any other white ethnicity--the Irish were thought to be level with, or only slightly above, the black race.

Wilde tended to identify with his British side, and was troubled by this caricature. But it didn't stop him from emphasizing his Celtic side, and getting political about Home Rule, in his speeches in towns with large Irish populations such as St. Paul and San Francisco. And it didn't hurt that his mother had been a famous Irish patriot decades ago. (In fact, before the tour she was probably a more noted public figure than Oscar was.)

And later, as Wilde traveled through the deep South, he would identify with the concept of the Lost Cause, which was the South's view of itself and its reasons for fighting in the Civil War. (Wilde had a late uncle who'd emigrated to America and become a rich and respected plantation owner in New Orleans, though that money was long gone--the Civil War hadn't helped, and in any case, Wilde men tended to be profligate.) Wilde even met with Jefferson Davis. When asked about the Confederacy, Wilde would generally turn the question around and relate it to the Irish fight for independence.

By the time Wilde returned to England, he'd made his reputation. Legends grew out of the tour, many of which, in fact, were burnished by Wilde in his British speaking tour on his impressions of America. (Mendelssohn is good at distinguishing the legends--many of which are still believed today--from the facts.) And Wilde had also learned a lot about entertaining audiences, which he put to good use when he wrote his social comedies for the West End stage in the 1890s.

Here Mendelssohn perhaps overextends her argument, stating Wilde's plays were strongly influenced by minstrel shows. It's not entirely absurd--Wilde's shows employ stock figure and plenty of jokes, and there were even critics at the time who noted the relationship--but I think she overstates the case.

Anyway, a fine book. There's a lot out there about the man, but Making Oscar Wilde truly breaks new ground.

5 Comments:

I saw Patience last year, but I didn't know that Wilde actually toured with D'Oyly Carte!

Here is the greatest of the Savoyards, John Reed, as Bunthorne. The whole song is great, but if you don't like the slow part, skip to 1:42.

Lyrics here.

He didn't tour with the D'Oyly Carte G&S company, but he did have the same backing.

I went on a Dublin Literary Pub Crawl in October and they spent a fair time on bit where Oscar outdrank some Colorado miners bored by his talk

NE guy

The Colorado stuff became the central legend of Wilde's tour. Some of it is true--and Wilde did keep up with them, drink for drink--but Oscar himself embellished his reception there quite a bit.

Thank you, LAG. A terrific piece.

Post a Comment

<< Home