The Beatles' story has been told so many times you'd think there's no room for another book. But Mark Lewisohn's

The Beatles: All These Years, the first in the

Tune In trilogy, isn't just another book. In fact, if may end up being

the Beatles book. Certainly this volume is as good as anything that's been written on their early years.

At 900+ pages, it better be. It may be lengthy, but it never feels overlong, or padded. There are revelations on practically every page. Lewisohn, a recognized expert on the Beatles, puts to rest some myths (young John having to choose between his mom and dad, Pete Best being fired for being too handsome and about a hundred others) and puts things in a wider context than ever before. As he says, "Let's scrub what we know, or think we know, and start over."

The four Beatles, in the years before worldwide fame, come to life. And while John, Paul and George get most of the attention, this books keeps us apprised of Ringo's action along the way--every other book I've ever read tends to only catch up with his story when he's chosen for the band, years after the other three had been performing together.

Looking back at it all, the Beatles may seem inevitable, but, as

All These Years demonstrates, there were numerous points where it could have fallen apart. First, of course, you have them as kids hearing this amazing thing called rock and roll, and deciding along the way this will be their life. Lewisohn is good describing when each new record came out, and how the boys responded. John started a band with his friends, and, slowly, the rest happened. The big question at first was should John bring aboard this kid Paul--he's a better musician than John, so does John want to remain top dog, or have the band be better? The same urge to improve the band also had him force out members, including close friends. And then Paul brings in an even younger kid, George, but he's got the chops. Then, years later, they already loved Ringo, especially George, and so at the last possible second he was Beatlized.

In fact, in early 1960, when John, Paul and George and whoever else they might have were scrambling to get any gig, Ringo was one of the top drummers in Liverpool. And yet even he didn't think there was much of a future in this business--no one thought there was a future in rock and roll then. Each of the four had to decide for themselves to voluntarily leave the race for a conventional job and go with the unknown. Even in the years when they were making better money than their parents, but before the recording contract, it was touch and go.

One big turning point is when John, Paul and George got booked in Hamburg. Not that they were such a hot band then, but there was a connection established where Liverpool would send rockers over to play in the rough St. Pauli district. The trio couldn't go without a drummer, and there was Pete Best, who had a set, and who had a mom, Mona, who booked them at her club, so that was good enough--especially since no one else was available.

The boys played long and hard in Hamburg. Their talents were being honed, and when they come back to Liverpool, they were the best band around. Pete, however, was only a so-so drummer, and not really one of the guys--he was shy and kept to himself. They always knew they'd replace him, but they didn't have another drummer handy and Pete and Mona still got them bookings, so nothing was done due to inertia and cowardice. (The Beatles often come across as pretty cold in this book, and that's probably right. They were dynamic, fresh and charming, but they could be cutting, and freeze you out if they didn't like you. For that matter, John was such a troublemaker that the parents of almost everyone who came into his orbit in the early days warned their kids to stay away.)

You'd think they were on their way to success, but they still didn't have a manager--at least not one they could work with--and their "screw you" attitude turned off a lot of bookers. But just in time (everything always happens just in time) Brian Epstein, a troubled man who owned a successful store--where the Beatles would hang out and listen to records--heard about them and saw them perform at their regular gig in the nearby Cavern. He was wowed, and decided to manage them (and not simply because he was attracted to John, as some book have reported), though he had no experience in that field. Not that The Beatles were pushovers. He had to convince them, and even after he signed them, they'd regularly make their complaints known. He was the perfect man for the job. The music business in England then (like everywhere else at all times) was filled with opportunists who'd squeeze a band dry and then go on to exploit another act, but Brian did it because he loved the boys and wanted them to go places. At the start, he'd often lose money covering expenses, but it didn't matter because he saw the big picture. He also was high class (compared to most of Liverpool), and his store, one of the biggest record-sellers around, meant he'd be taken seriously in London, the center of the British entertainment world.

But even then, it could have fallen apart. The Beatles soaked up influences and moved ahead at a regular pace, but they got tired of doing the same thing, and Brian booking them one place after another wasn't enough--they needed a recording contract. Not that records were considered big money--conventional contracts gave you pretty small royalties--but a record on the charts would mean better gigs with higher pay.

Brian got the back of the hand from EMI, the label he thought fit them best, but he managed to get them an audition at the other big British label, Decca. They came down to London and

recorded a demo in fairly uncomfortable circumstances (and still hadn't gotten around to cutting Pete). They were rejected. And then were rejected at every small label after that.

This is a band that's got a huge following in Liverpool, and has a new and exciting sound--even writes some of their own numbers, unheard of at the time. So why the rejection? First, of course, the Decca tape isn't them at their best. Also, down in London, Liverpool meant nothing. Then, of course, no one wants to take chances, and their sound was different. Weren't guitar groups on their way out, anyway? Then there's that creepy name. Plus, when you said "group" in those days, people would ask "instrumental or vocal?" Acts were usually solo, or a lead singer with a backup band. The Beatles had three lead singers, did a wide variety of music, and played their own instruments. It was hard to know what to make of them.

Once again, this could have been the end. But Brian had a last-chance opportunity back at EMI. While there, he also met with some publishers associated with EMI (it wasn't a planned meeting, but someone suggested it). They liked the band's original songs and thought they could push them. (In those days, publishers made money selling sheet music, and having other artists perform the same songs--this would change soon. In fact, the Beatles would change everything about the music business.) Brian also saw George Martin, probably the most creative producer at EMI. He was in charge of the relatively minor Parlophone label, but he put out quite a few imaginative pieces there, including a lot of comedy bits with members of the Goons. Martin, however, wasn't impressed with the acetate made from the Decca audition.

So how did they get the contract? This is a story I believe Lewisohn breaks. The song pluggers Epstein met convinced EMI to take a flier on the band, figuring they could get publishing rights and make some money from Lennon and McCartney. (Ironically, the Beatles went with another publishing company when they hit, on the advice of George Martin.) And it would take almost nothing from EMI. The company's contract promised their artists very little--only a few recordings and minuscule royalties. Why not? After they got the contract, that's when they fired Pete and convinced Ringo to join. Of course, the professionals at Decca and EMI had noted Pete was no good, so even if they'd stuck with him, he wouldn't have been used in the studio.

So in June 1962 the boys went down to London and recorded a few sides--Lennon and McCartney originals "Love Me Do," "P.S. I Love You" and "Ask Me Why" as well as a club favorite, the cha-cha-boom number "Besame Mucho." The question is why did they record so many originals? The regular procedure was the producer would find a song, an artist who fits, make the arrangement and put out the record. Artists didn't write their own stuff, and Martin didn't think much of their songs to begin with. The answer to this mystery is, once again, the publishers convinced EMI to put out an original.

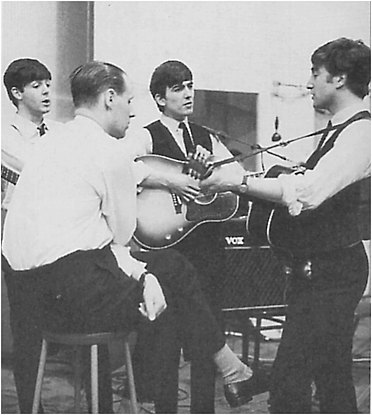

The session wasn't a big deal to Martin. He wasn't at the board and showed up late. And when he got there and heard the results, he wasn't impressed. But then the Beatles came up to the booth. Martin explained, rather brusquely, how things would go. When he was done, he asked the band if there was anything they didn't like. Harrison responded he didn't like Martin's tie. That broke the ice. They started talking, and, like so many others, Martin found them uncommonly charming--the kind of people you want to hang out with.

Though it was unusual, he wanted them to come back and give it another shot. He found a song he thought had hit written all over it--"How Do You Do It?" The Beatles dutifully learned it, but hated it--it was a soft sort of tune that embarrassed them. They recorded it in the next session, and also had another bash at "Love Me Do." Ringo had been a bit erratic at first in their previous session, and to his horror, Martin had brought in his own professional drummer--was this how things were to be? In fact, it took Ringo years to get over it, and even when they became the biggest band in the world, he'd still occasionally bring it up with Martin.

The Beatles wanted "Love Me Do" to be the release--and the push by the music publishers helped guarantee it, over George Martin's wishes. Because Mitch Murray, the songwriter of "How Do You Do It?," wasn't willing to see his hit be wasted in a weak version on a B-side, that recording was never released and "P.S. I Love You" was used. (Martin was right about "How Do You Do It?"--he gave it to Gerry And The Pacemakers for their debut single in 1963 and it went to #1 in Britain.)

Martin didn't figure "Love Me Do" would do anything--and if it hadn't, that would have probably been the end of their recording career, since EMI didn't owe them anything more. But thanks to the Beatles tremendous popularity in the North, it sold fairly well, staying on the charts for months and making the top twenty. (Lewisohn puts to rest the rumor than Brian ordered so many copies of the single that it charted). Martin was surprised, and started to take this new band seriously. Thus, something unusual began--a band that wrote its own singles. It's doubtful another producer would have allowed it, or worked so well with the group, giving them the freedom to grow (and not taking partial or full credit for songwriting royalties, as was common then).

John had a new Roy Orbison-style song called "Please Please Me." Martin suggested they speed it up. They recorded it in November. Everyone was sure this was a #1 hit--and they were right. But it wouldn't be released until January, so they were sitting on it, trying to figure out how best to exploit it. One idea that Martin had--make an LP. This might seem the normal thing to do, but back then pop music was about singles. Albums were for serious music, stuff adults bought. Sure, if you had a few hits, maybe you'd record some filler and put out an album, but the singles were what kids bought, and what you concentrated on.

He considered taping them live in the Cavern since the Beatles said they were best live. But that was based on their early studio experiences. They hit the sweet spot with "Please Please Me" and from then on were a true studio band. Anyway, the sound was lousy down in the Cavern, so Martin suggested they pick some numbers from their ever-evolving stage show (the Beatles always stayed ahead of the competition) and write some new numbers, and they'd record ten songs in one day.

So it's late 1962, the word is spreading. It looks like they'll conquer England in 1963, and, what they probably didn't guess, they'd conquer America and the world in 1964. (EMI mailed its hit records each week to America, but a jerk named Dave Dexter, Jr., who loved jazz, rejected just about every pop record they sent. Amazingly high-handed, considering EMI owned Capitol. The Beatles early singles were shunted off to minor labels such as Swan and Vee-Jay, until the pressure became too great and they broke in America. Dexter would go on to rip apart their British albums, which generally included 14 songs, and create special American versions which featured only 11 songs--even less on soundtrack albums--in the order he determined.)

Anyway, as 1962 ends, so does the book. And even though it's over 900 pages, I wanted more. The rest of their story will be the Beatles the world knew. But somehow I think Lewisohn has plenty to tell us that we don't know.